Bald One of Hathor

Among the many sculptural treasures of Ancient Egypt, few are as quietly evocative as the statues known as the “Bald One of Hathor”. These figures, though not divine themselves, were profoundly entwined with the sacred world of temple ritual and devotion. Most often depicted as shaven-headed men in attitudes of piety or offering, they represent ritual servants of the goddess Hathor — one of the most beloved and complex deities of the Egyptian pantheon.

Hathor, whose worship flourished from the Old Kingdom onward and peaked during the New Kingdom (c.1550–1070 B.C.), presided over music, love, fertility, beauty, and joy, while also extending her protection to the dead and guiding them into the afterlife. Her temples, such as the magnificent sanctuary at Dendera, were centres of divine music, ritual ecstasy, and formal offerings. Within such sanctuaries, the “Bald One of Hathor” played a unique and essential role.

These shaven figures were likely temple musicians, priests, or ritual performers, whose lack of hair signified ritual purity and dedication to sacred duties. Their statues, carved in fine limestone, alabaster, or occasionally wood, are modest in scale yet elegant in design — often shown seated cross-legged, kneeling, or standing with offerings in hand. Their features tend to be idealised, and their expressions serene, radiating the calm assurance of those perpetually in the service of the divine.

The “Bald Ones” appear most prominently during the Middle and New Kingdoms, with notable examples discovered at Dendera and other Hathoric sites. Some bear inscriptions identifying them by name and office, revealing personal devotion as well as formal priestly rank. These figures were not merely artistic representations, but rather ritual objects believed to participate in ongoing acts of worship, even after death. Through the magic of inscription and form, the statue could continue to serve Hathor for eternity, ensuring spiritual favour and sustenance in the next life.

In their understated beauty, these statues reflect a central truth of Ancient Egyptian belief: that the boundary between mortal and divine could be bridged through ritual, purity, and eternal service. To be the “Bald One of Hathor” was not only to serve a goddess in life, but to dwell in her music and light forever more.

Steatite Head, c. 1336–1250 B.C.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York houses this distinguished example (64.22) of a “Bald One of Hathor” statue. This figure is carved from steatite, a soft metamorphic rock often referred to as soapstone, prized in Ancient Egypt for its smooth texture and ease of carving.

While specific details about this particular statue’s provenance are not readily available, such statues are typically found in temple complexes and tombs, especially those associated with the cult of Hathor. Their placement and function are closely tied to the religious roles these figures played, both in life and in the Afterlife.

As with other heads of such, this one in particular depicts a male figure with a horse-shoe hairline (bald on top, hair on sides), symbolizing ritual purity and dedication to the goddess Hathor.

Statuette of Iner

This finely carved statue represents a minor temple official named Iner, who bore the title of “sauty” — a guardian or keeper within the sacred precinct. Iner is depicted holding a sistrum, the ceremonial rattle closely associated with the goddess Hathor. This particular instrument is adorned with a representation of the goddess herself, identifiable by her distinctive cow’s horns and elegantly styled wig, both hallmarks of her iconography.

The statuette is made of granodiorite, and measures at 17 cm x 37 cm x 20.5 cm. The location of which the figure was discovered is unknown, it arrived at the Egyptian Museum of Turin after it was purchased by Bernardino Drovetti in 1824.

Iner raises one hand to his mouth in a traditional gesture of supplication, silently inviting passersby to place offerings upon the statue — food, incense, or other tokens of reverence. This gesture was not merely symbolic; it activated the statue as a participant in the living cult, encouraging a bond between the viewer, the divine, and the commemorated individual.

Such statues, often placed within temple courtyards or processional paths, served a dual purpose: they maintained a spiritual connection with the gods, particularly Hathor, while also engaging with the human world — with pilgrims, worshippers, and temple-goers. Through this act of eternal presence, Iner sought favour in the afterlife and a share in the divine offerings made in the sacred space.

Shaven Heads and Sacred Service

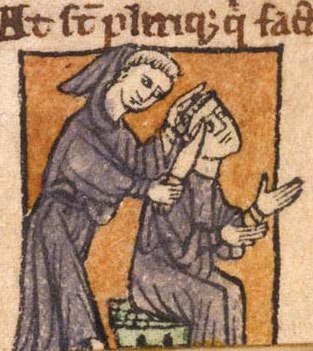

Two seemingly unconnected traditions, separated by both time and culture, offer a compelling visual and symbolic parallel: the shaven-headed temple servant of Ancient Egypt, known as the “Bald One of Hathor”, and the tonsured monk of medieval Christendom. Though their worlds were vastly different, their shared gesture speaks to a universal impulse — to outwardly reflect inner sanctity.

The statues of the “Bald One of Hathor” from Ancient Egypt present a striking image: a shaven-headed temple servant, poised in devotion, often holding ritual instruments such as the sistrum. The shaved head in this context symbolised ritual purity, a visible marker of the individual’s consecration to the goddess Hathor and his readiness to participate in sacred rites.

This imagery naturally invites comparison with the familiar figure of the medieval Christian monk, whose partially shaven head — the tonsure — signified humility, obedience, and devotion to God. Though visually and symbolically similar, there is no evidence to suggest a direct historical link between these two traditions. The tonsure, which developed independently within early Christian ascetic communities, likely drew inspiration from Greco-Roman customs rather than Egyptian temple practices.

Yet, the resemblance is more than superficial. Across time and culture, the act of removing hair has repeatedly served as a powerful emblem of spiritual transformation and separation from the worldly. Whether in the shadowed courtyards of Egyptian temples or the cloisters of medieval monasteries, the shaven head has come to signify a life dedicated to the divine.

Cutting or removing hair has been a religious practice across many cultures, and while the meanings vary, they often centre around transformation, purity, humility, and sacrifice. Hair is often associated with vanity, pride, or earthly identity. Removing it is a way of letting go of ego and worldly attachments.

In religions such as Hinduism, Islam, and Judaism, cutting or shaving hair can signify spiritual cleansing. For instance, pilgrims on the Hajj shave their heads as an act of purification and renewal. Similarly, Ancient Egyptian priests shaved their entire bodies — including the head — as a sign of ritual purity before entering sacred space.

Hair-cutting, therefore, often marks a rite of passage — the entry into a new spiritual stage or commitment. Buddhist monks and nuns, for example, shave their heads when they take their vows, symbolising their departure from worldly life. In some cultures, hair can even be seen as a precious offering. In the Vedic tradition of India, hair might be offered to the gods in fulfilment of a vow, much like a sacrificial gift.

All in all, from Ancient Egypt to present day, cutting hair in religious contexts is never merely cosmetic. It is a deeply symbolic act — a gesture of devotion, an external sign of internal change, and often, a way to step away from the ordinary and draw closer to the divine.